By this time we’ve pretty much been beaten over the head with the whole “farm to table” concept. The shorter the daisy chain between the two, the better the end result. No freezing, no canning, no drying…no international shipping, no impersonal buying relationships, no commodities. And if we take that conversation one step further, there’s that whole stigmatized matter of terroir we can take up as well. My Jersey tomato tastes completely different from a Florida tomato, not that I’d ever know unless I hit a farmer’s market because the faux fruit that lines my produce section is picked green somewhere in Mexico and sprayed with ethylene gas on its way here so that at the very least it looks ripe. We often drop the term terroir when we wax poetic about wine, but the long and short is that terroir is at the heart of anything sprung from the earth, not just grapes. Even pigs—raised, slaughtered and cooked identically in 2 different countries—will taste different because of the local grasses, nuts and mushrooms they ate.

But ask a craft beer geek about his favorite brews and he’s likely to tell you that it was not only made with wheat from Bavaria, orange peels from Tahiti, and water from an ancient, remote spring somewhere in the backwoods of East Buttfuck, Belgium…he’ll also tell you that it was aged in old Tennessee bourbon barrels and best yet, that it was made with dried, hamster-droppings-like pellet hops. The massive growth that we’ve seen in the craft beer industry has been matched by its insatiable jones to use foreign, exotic ingredients pretty much negating any possibility of “beer terroir.” Add to that those damned hop pellets and at best you’ve got the alcoholic equivalent of a mutt—or at worst, one of those really horrific muzak tunes that defies identification.

But ask a craft beer geek about his favorite brews and he’s likely to tell you that it was not only made with wheat from Bavaria, orange peels from Tahiti, and water from an ancient, remote spring somewhere in the backwoods of East Buttfuck, Belgium…he’ll also tell you that it was aged in old Tennessee bourbon barrels and best yet, that it was made with dried, hamster-droppings-like pellet hops. The massive growth that we’ve seen in the craft beer industry has been matched by its insatiable jones to use foreign, exotic ingredients pretty much negating any possibility of “beer terroir.” Add to that those damned hop pellets and at best you’ve got the alcoholic equivalent of a mutt—or at worst, one of those really horrific muzak tunes that defies identification.

It was only a matter of time before forward-minded brewers started looking at their neighboring winery’s vineyard down the road, scratching their heads, and asking themselves why the hell they weren’t doing the same thing. It was only a matter of time before experimenters started eschewing hop pellets for the freshness of “wet hops” in their worts even if they were mocked for being wasteful. It was only a matter of time before the terms “homegrown” and “appellation” started being used on beer labels. And it was only a matter of time before the craft beer world sat up and took notice of just how unlocal their beer was, even if (or despite that) it was made by a local brewery.

The process of wet hopping has nothing to do with actual wetness—nobody’s soaking hops in water, spraying them down or showing them porn. Wet hops are simply the antithesis of the dried hop pellet…they’re fresh. And despite the fact that there are several arguably logical reasons not to use fresh hops at the start of a boil (the mess fresh hops leave behind, the steam and froth created by the natural water in the hops, and the waste of aromatics and flavors), brewers everywhere are scrambling to become wet hoppers, racing their hop-filled trucks from farm to brewery at speeds that would probably scare the shit out of Dale Earnhardt, Jr., just so they can get them into the kettle as green as possible. And make no mistake, there is a notable difference in fresh-hop beers. They tend to be more herbaceous, earthy and spicy.

The process of wet hopping has nothing to do with actual wetness—nobody’s soaking hops in water, spraying them down or showing them porn. Wet hops are simply the antithesis of the dried hop pellet…they’re fresh. And despite the fact that there are several arguably logical reasons not to use fresh hops at the start of a boil (the mess fresh hops leave behind, the steam and froth created by the natural water in the hops, and the waste of aromatics and flavors), brewers everywhere are scrambling to become wet hoppers, racing their hop-filled trucks from farm to brewery at speeds that would probably scare the shit out of Dale Earnhardt, Jr., just so they can get them into the kettle as green as possible. And make no mistake, there is a notable difference in fresh-hop beers. They tend to be more herbaceous, earthy and spicy.

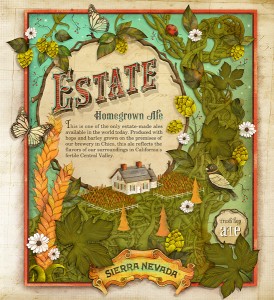

But not to be outdone by their fellow hop hustlers, breweries like Sierra Nevada and Rogue are taking it to the dirt themselves, growing their own barley and hops. Sierra’s “Estate” ale (you gotta love the winespeak) is made from organic wet hops and barley that are both grown at the brewery. Rogue, on the other hand, has several homegrown beers, otherwise known as the Chatoe Rogue creations (more play on winespeak): Dirtoir Black Lager, OREgasmic Ale, Single Malt Ale, Wet Hop Ale and Creek Ale. Will I deny that I love Dogfish Head’s Pangaea, which is made from ingredients from each of the 7 continents? Nope—it’s fantastic. But there’s certainly something to be said for trying not only to keep it local, but further to keep it in your own little microcosm of dirt. In an industry swimming in beers that, as artisanal as they may be are still indistinguishable by origin, how many breweries can actually claim terroir? Just as important…do you care?

{ 8 comments… read them below or add one }

I guess in some grand sense I do care, but yet my buying practices in no way reflect that. See both the Chatoe Series from Rogue and Sierra Nevada’s Estate Ale are kind of like the brewery’s experiments. I’ve heard they are just mediocre too. This has led me to pass them over time and again. I actually have access very readily to both these beers and I have not taken advantage of it. I think in the final analysis it is the quality of the product that matters most. If you’re NJ Tomato tasted like shit you probably wouldn’t buy them. So there is the rub. Quality, not concept tends to drive our purchasing decisions. Just my 2 cents.

I think your point is totally valid as far as quality driving purchase decisions. God knows there are countless bottles of “biodynamic” wines that are undrinkable no matter how laudable the concept of it is. You need to follow up the concept of “homegrown” beer with a good product. That being said, though, there is certainly an ecological price we pay for importing exotic ingredients from every corner of the world, isn’t there?

I agree that there is a price to be paid for the crazy beers out there. Now Whiskey is very terroir in its distilling, and the ingredients that go into the various mash bills, so I feel somewhat vindicated by the fact that I am the Whiskey Brother! 😉

I think what we have here is a good start. I haven’t tried any of these beers, but as with so much that happens in craft beer, the idea is important enough by itself. The crucial thing it seems, is to change the way we think about malt. We’re still making craft beer with mega-brewery malt production (in almost every case). I doubt if any homebrewer, or beer enthusiast knows which variety of barley their malt is produced with. The truth is, there hardly ever is one, because they are almost always blended to produce repeatable results. Can you imagine if every wine was made with different generic, “juice blends” designed by corporate wine-growers to produce varying, but predictable results? Do you ever hear from a brewer “Oh, this was a bad year for brewing, the barley crops turned out weird because of the right rain/sun levels, etc…”?

Not that I think predictability is a bad thing, I just think this is another area that craft beer could explore, like yeast culturing. I don’t think every big craft brewery would be able to make their own barley, but I would love to see smaller regional maltsters getting in on the action, or maybe something like american versions of marris otter or golden promise. I think the craft market would be able to support it.

I couldn’t agree more….it is certainly worth exploring. And to your point, a good deal of the conglomerate Champagne that works it’s way into our homes comes from “juice blends” designed specifically to defy the effects of a possible “bad year” and I can think of plenty of other wineries that do the same, but thankfully, as you said, it’s not EVERY wine’s case. I look forward to where this could go, as long as it goes there because of its philosophy and not its marketability.

I once vacationed at the East Buttfuck Springs Marriot Resort and Lodge in Belgium… At dinner one night I told them to surprise me with an imported beer and they gave me a Coors Light…Fucking Belgian bastards…

BTW, the breakfast food is just known as waffles there…

So good I’m actually speechless.

I concur, it is only a matter of time, and it is – forward into the past – on the old east coast as all the barley (incl. malting), hops growing, and both wild yeast and cultured yeast were originally done around here long before it moved west to the cheaper lands/better climate. It will take some capital for processing machinery to get this up to compete with existing suppliers, but there seems to be a desire to bring it all back here. I’d like to be part of that movement.

{ 1 trackback }